Top Secret Tomfoolery

Here goes:

9-11 Commission Report, Chapter 11, "The Millenium Exception" (all bold added by us)

Keep in mind, we're definitely not suggesting that intelligence agencies share more information with American citizens (certainely not more than "We're raising the terror level, because, well, we have our reasons" because that would counter-productive).Before concluding our narrative, we offer a reminder, and an explanation, of the one period in which the government as a whole seemed to be acting in concert to deal with terrorism-the last weeks of December 1999 preceding the millennium.

In the period between December 1999 and early January 2000, information about terrorism flowed widely and abundantly. The flow from the FBI was particularly remarkable because the FBI at other times shared almost no information. That from the intelligence community was also remarkable, because some of it reached officials-local airport managers and local police departments-who had not seen such information before and would not see it again before 9/11, if then. And the terrorist threat, in the United States even more than abroad, engaged the frequent attention of high officials in the executive branch and leaders in both houses of Congress.

Why was this so? Most obviously, it was because everyone was already on edge with the millennium and possible computer programming glitches ("Y2K") that might obliterate records, shut down power and communication lines, or otherwise disrupt daily life. Then, Jordanian authorities arrested 16 al Qaeda terrorists planning a number of bombings in that country. Those in custody included two U.S. citizens. Soon after, an alert Customs agent caught Ahmed Ressam bringing explosives across the Canadian border with the apparent intention of blowing up Los Angeles airport. He was found to have confederates on both sides of the border.

These were not events whispered about in highly classified intelligence dailies or FBI interview memos. The information was in all major newspapers and highlighted in network television news. Though the Jordanian arrests only made page 13 of the New York Times, they were featured on every evening newscast. The arrest of Ressam was on front pages, and the original story and its follow-ups dominated television news for a week. FBI field offices around the country were swamped by calls from concerned citizens. Representatives of the Justice Department, the FAA, local police departments, and major airports had microphones in their faces whenever they showed themselves.42

After the millennium alert, the government relaxed. Counterterrorism went back to being a secret preserve for segments of the FBI, the Counterterrorist Center, and the Counterterrorism Security Group. But the experience showed that the government was capable of mobilizing itself for an alert against terrorism. While one factor was the preexistence of widespread concern about Y2K, another, at least equally important, was simply shared information. Everyone knew not only of an abstract threat but of at least one terrorist who had been arrested in the United States. Terrorism had a face-that of Ahmed Ressam-and Americans from Vermont to southern California went on the watch for his like.

In the summer of 2001, DCI Tenet, the Counterterrorist Center, and the Counterterrorism Security Group did their utmost to sound a loud alarm, its basis being intelligence indicating that al Qaeda planned something big. But the millennium phenomenon was not repeated. FBI field offices apparently saw no abnormal terrorist activity, and headquarters was not shaking them up.

Between May 2001 and September 11, there was very little in newspapers or on television to heighten anyone's concern about terrorism. Front-page stories touching on the subject dealt with the windup of trials dealing with the East Africa embassy bombings and Ressam. All this reportage looked backward, describing problems satisfactorily resolved. Back-page notices told of tightened security at embassies and military installations abroad and government cautions against travel to the Arabian Peninsula. All the rest was secret.

The End

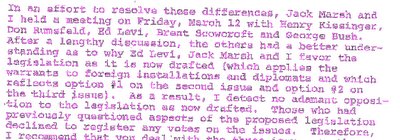

Moreover, aside from keeping all intelligence secret, we would never suggest that George H. W. Bush and Donald "The Don-Man" Rumsfeld fought against a bill that would regulate domestic spying, say, during the Ford Administration, but were finally convinced to support it. They certainly weren't convinced by the fact that the "cons" of domestic spying, if such a thing existed, were outweighed by the "pros" of domestic spying.

If any of that were true, it might suggest that many of the people still in the Bush Administration/family already acquiesced to the idea that there are bad aspects to having to get a warrant to spy on Americans but, moreover, that the positive aspects exceed and cancel them out.

If any of that were true, it might suggest that many of the people still in the Bush Administration/family already acquiesced to the idea that there are bad aspects to having to get a warrant to spy on Americans but, moreover, that the positive aspects exceed and cancel them out.Then again, we're not professionals. What do we know? This (national intelligence situation, no pun intended) all just seems counter-productive to us, and we'd like to (in this environment of spirited debate) put in our two cents. Though we know, in our heart of American hearts, that being secretive and closed up is probably the best way to run one of the largest and most powerful countries in the world.

Technorat tags:nsa, Bush, spying, terrorism

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home