Iran also handed over documents and granted interviews with several senior officials thought linked to black market purchases of uranium enrichment technology, one diplomat said.

But at the same time, the regime also takes a harsh tone about the West.

On Wednesday, more than 10,000 demonstrators shouted "Death to America" and "Death to Israel" in front of the former U.S. Embassy _ the largest such demonstration in years.

Hard-liners organize protests at the site annually to mark the anniversary of the embassy's seizure on Nov. 4, 1979, by militants who held 52 Americans hostage for 444 days. The United States broke relations with Tehran after the takeover, and they have not been restored.

Demonstrators carried a large picture of Ahmadinejad emblazoned with his quote, "Israel must be wiped off the map." They burned U.S. and Israeli flags and effigies of President Bush and Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon.

"We have to continue our confrontation with the United States and Israel," the hard-line newspaper Jomhuri Eslami said in an editorial.

--

Ali Akbar DareiniWashington PostNovember 2, 2005

"If, for whatever reason, the Security Council is unable to redress the grievances of the Palestinian nation, it should at least pass the appropriate resolution to condemn the repeated commission, particularly over recent days, of crimes like the bombardment of Palestinian areas and homes and the massacre of innocent women and children, upon the direct orders of this terrorist regime."

The statement further said that the position of the Islamic Republic of Iran on the situation in the Occupied Territories was clearly expressed by President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad at the 60th session of the U.N. General Assembly, to wit:

"In Palestine, a durable peace will be possible through justice, an end to discrimination and occupation of Palestinian lands, the return of all Palestinian refugees, and the establishment of a democratic Palestinian state with Al-QodsSharif [Jeruselum] as its capital." The Islamic Republic of Iran is committed to its obligations under the United Nations Charter and has never used or threatened to use force against any other state.

Milad looked at me either like he’s wary, amazed, or both.

“Alors,” he said, “Pourquoi t’as quitté ton pays? Tu ne l’aimes pas?” He furrowed his brow.

I told him that I hadn’t become an ex-pat because of some disdain for the US. I had left, if anything, because I felt it was my responsibility. I told him that I wanted to see the entire world, that I want to be everywhere and experience life in all its sorts. It was because of that desire and all that is going on in the world right now, I told him, that I felt like it is my task to go and see the world.

Milad nodded and told me that that was a venerable outlook.

I told him that I hoped it would work out.

The metro arrived and he motioned for me to get on first. We were both silent, waiting for the doors to shut. Once the train started moving, I continued, telling him I have problems with things that go on in my country but that, if I’ve learned anything from my experiences abroad, every country is generous in presenting problems that seem life-threatening.

I stuttered when I told him that I think all countries have serious problems, and I wanted to say that America’s are more serious only because everybody is focused on the US. I was worried, though, that he was going to think I was brushing off the problems between the US and the world as a formality or that I was overestimating other problems around the world.

“T’as raison,” Milad replied before I could continue.

I asked him why he had left Iran, and he smiled and told me that it was the same reason I had: “une fille.” I had already told him about Fanfan and I.

Milad had met his fiancé in Iran while she was visiting relatives, and they had kept in contact with each other. Every time she came back to Iran, they spent time together. She’s French, so he moved here to study law and marry her. He laughed and told me he’s studying law for the same reason I’m studying philosophy, but I clarified that I’m studying philosophy in France for the same reason that he’s studying law here.

“N’est pas?”

“Oui, oui.” He nodded, “D’accord. Donc, tu aurais resté aux Etats-Unis si tu n’est pas venu en France?”

I told him that I would have left anyway, repeating that I want to see the world. The difference is that I would have gone to Asia or somewhere further away like that. The latter was a veiled reference to that fact that I want to go to the middle east, but, for some reason, I didn’t find it prudent to tell him. It wasn’t because I thought he would tell me not to, but because I had this stupid idea that I was trying to suck up to him or something.

“Tehran te manque?” I asked him.

He sighed and said he like France, but of course he misses Tehran. His family and his friends are there. He asked me if I missed my home, and I said the same thing. It’s what makes living abroad the most bitter-sweet thing in the world, I told him, being always inundated with things that are fascinating but at the same time wanting to share it with people that are far away.

The doors of the train shut, and the train started moving. Neither one of us said anything. As the train slowed at the next stop, Milad smiled and said that it was really pleased to have met me. I returned the compliment, which was an understatement.

“Bon weekend,” he said and held out his hand.

I shook his hand, “Toi aussi, à la prochaine.”

Milad got of the metro, and I sat there with a hundred questions about the world that I hadn’t felt it a good idea to ask in the first conversation, but knowing also that the newspaper doesn’t give the full picture. I like to think that he was thinking the same thing.

This was the first of five conversations with Milad, and there has still been no mention of empire, nuclear weapons, Bush, Israel, or Palestine. That’s something that people have to remember.

First of all, sorry we've been away for some time. There has been much sickness and frustration in Paris, so our beloved Editor has been unable to keep up with the sheer amount of earth-shattering information we have provided.

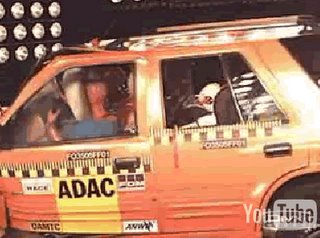

First of all, sorry we've been away for some time. There has been much sickness and frustration in Paris, so our beloved Editor has been unable to keep up with the sheer amount of earth-shattering information we have provided. As the LA Times explained today, the Chinese are moving into a new market, or at least moving that market over to the West. This market is, of course, automobiles. With poetic names like Landwind (whatever that means), these cars are bursting to be sold in the West, and I mean that literally. The first crash-test of the Landwind (precursor to the Mountainsnow, and Riverbreeze) scored a big, fat ZERO the day before it was to be presented in a German car show.

As the LA Times explained today, the Chinese are moving into a new market, or at least moving that market over to the West. This market is, of course, automobiles. With poetic names like Landwind (whatever that means), these cars are bursting to be sold in the West, and I mean that literally. The first crash-test of the Landwind (precursor to the Mountainsnow, and Riverbreeze) scored a big, fat ZERO the day before it was to be presented in a German car show.